"Not only are ecosystems more complex than we think, they are more complex than we can think."

- Jack Ward Thomas

- Jack Ward Thomas

When I first moved to Montana out of the Marine Corps in 1985 I was determined to learn all I could about elk. In addition to roaming the wilds and observing the magnificent animals year round, I also read the hefty treatise “Elk of North America: Ecology and Management,” committing myself to daily readings like one might approach bible study. One of the disciples of the book was Jack Ward Thomas.

Years later I took a job as the conservation editor for the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation's Bugle magazine, researching and writing articles about all things elk – natural history, ecology, behavior, habits and habitat and management. Naturally, one of my primary sources was Jack Ward Thomas.

In 2001, I had the honor of working with Jack, co-authoring a chapter to an updated version of "Elk of North America," this one called “North American Elk: Ecology and Management.”

Needless to say, I learned a lot from Jack Ward Thomas. A lot of people did.

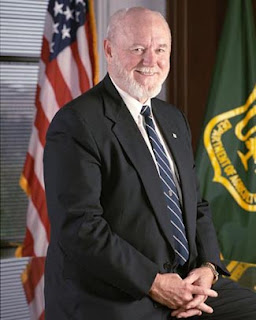

On Thursday, May 26, after a long struggle with cancer, Jack Ward Thomas died at his home in Florence, Montana, surrounded by the love of his family. He was 81. He was a husband, father, veteran, scientist, author, professor and leader who contributed immensely to our knowledge of wildlife, forests and ecosystems and worked tirelessly to not only pass that knowledge on to others, but also to ensure that the science shaped management policies to help protect and enhance the future health of our wildlife and wild places.

After earning a bachelor’s degree in wildlife management from Texas A&M, in 1951, he spent the first ten years of his career with the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department before moving to West Virginia to work as a research biologist with the U.S. Forest Service. While there, he earned a master’s degree in wildlife ecology from West Virginia University. He then went on to head up a Forest Service research unit at the University of Massachusetts where he also earned his PhD in forestry in 1972.

In 1974, he moved to La Grande, Oregon to work as the chief research wildlife biologist and program leader at the Forest Service’s Forestry and Range Sciences Laboratory. It was in Oregon where Jack conducted ground-breaking research on the impacts of logging, roads, off-road-vehicles and other factors on elk and elk hunting. His Blue Mountains Elk Initiative brought together researchers, land managers and wildlife managers in a monumental, collaborative research project that helped define terms and concepts such as elk vulnerability, habitat security, habitat effectiveness and how all those variables and more effect elk and elk hunting.

Jack also helped launch the Starkey Project in Oregon, a joint wildlife research project conducted by the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife and the Forest Service. The project measured the response of deer and elk to intensively managed forests and rangelands as well as open roads and various types and levels of motorized use. One of the most comprehensive field research projects ever attempted, studies examined key questions about elk, deer, cattle, timber, roads, recreation uses and nutrient flows on National Forests.

Jack also helped launch the Starkey Project in Oregon, a joint wildlife research project conducted by the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife and the Forest Service. The project measured the response of deer and elk to intensively managed forests and rangelands as well as open roads and various types and levels of motorized use. One of the most comprehensive field research projects ever attempted, studies examined key questions about elk, deer, cattle, timber, roads, recreation uses and nutrient flows on National Forests.

Results of Jack’s efforts were and continue to be worked into forest plans, and used by state wildlife agencies throughout the West to reduce the impact management activities can have on healthy, functioning ecosystems.

On December 1, 1993 Jack was appointed the 13th Chief of the U.S. Forest Service, a position he held until 1996. His approach to running the Forest Service can be summed up in his own words: "Always tell the truth and obey the law," and "We don't just manage land. We're supposed to be leaders. Conservation leaders. Leaders in protecting and improving the land."

After retiring from the Forest Service, he accepted a position as the Boone and Crockett Professor of Wildlife Conservation at the School of Forestry of the University of Montana in Missoula, Montana. (He once joked that "pontificating is easier than responsibility.") He held that position until 2006 when he officially retired.

An avid and passionate elk hunter himself, Jack worked hard to help ensure the future of our hunting heritage, and was a staunch defender of public lands. In 1995, at an Outdoor Writers Association of America conference I attended, Jack was asked if he thought proposals to sell our federal lands or turn them over to states was a good idea. This was his response:

On December 1, 1993 Jack was appointed the 13th Chief of the U.S. Forest Service, a position he held until 1996. His approach to running the Forest Service can be summed up in his own words: "Always tell the truth and obey the law," and "We don't just manage land. We're supposed to be leaders. Conservation leaders. Leaders in protecting and improving the land."

After retiring from the Forest Service, he accepted a position as the Boone and Crockett Professor of Wildlife Conservation at the School of Forestry of the University of Montana in Missoula, Montana. (He once joked that "pontificating is easier than responsibility.") He held that position until 2006 when he officially retired.

An avid and passionate elk hunter himself, Jack worked hard to help ensure the future of our hunting heritage, and was a staunch defender of public lands. In 1995, at an Outdoor Writers Association of America conference I attended, Jack was asked if he thought proposals to sell our federal lands or turn them over to states was a good idea. This was his response:

"Speaking for myself, I won't stand for it. I won’t stand for it for me and I won't stand for it for my grandchildren and I won't stand for it for their children yet unborn. This heritage is too precious and so unique in the world to be traded away for potage. These lands are our lands -- all the lands that most of us will ever own. These lands are ours today and our children's in years to come. Such a birthright stands alone in all the earth. My answer is not just no, but hell no!"

Those of us who enjoy wildlife and public lands owe Jack Ward Thomas a great debt of gratitude. His legacy lives on in the wild places we cherish.

Those of us who enjoy wildlife and public lands owe Jack Ward Thomas a great debt of gratitude. His legacy lives on in the wild places we cherish.

I first met Jack Thomas in LaGrande Oregon. Jack provided some data to Loren Hughes and I so we could appeal timber sales and prevent further damage from logging that was threatening elk habitat on the Wallowa Whitman National Forest. Jack's invaluable scientific contributions along with Loren's relentless devotion to elk conservation resulted in saving many important areas for elk in northeastern Oregon.

ReplyDeleteI had no idea that Jack was responsible for the Starkey Project!! Not sure how I missed that since we were using that reference at MWF AND we all talked to Jack regularly!

ReplyDeleteYes. When Jack was heading up the Forest Service's Pacific Northwest Research Station, he and Donavin Leckenby, of the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, developed the study plans and then Jack secured the approval and funding.

Delete